Imagine a world where the law was carved in stone, not just as abstract principles, but as a practical guide for daily life, dictating everything from property disputes to personal injury—and even the complex rights and responsibilities surrounding slavery. This wasn't a futuristic vision; it was the reality shaped by the Babylonian Empires and Hammurabi's Code, a groundbreaking legal framework that profoundly influenced ancient societies and continues to spark discussion about justice and human rights today.

While the concept of "rights" for enslaved people might seem contradictory through a modern lens, Hammurabi's Code offered a surprisingly nuanced, albeit often brutal, set of regulations that acknowledge slaves not just as property, but, in limited contexts, as individuals with certain legal standings.

At a Glance: Hammurabi's Code and Ancient Slavery

- Who was Hammurabi? The sixth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty (c. 1792-1750 BCE), known for his expansive empire and legal reforms.

- What is Hammurabi's Code? One of the earliest and most comprehensive written legal codes, comprising 282 case laws.

- Its Purpose: To establish justice, order, and regulate relationships across Babylonian society, including the complex dynamics between slave owners and enslaved individuals.

- The Role of Slavery: A fundamental aspect of the Babylonian economy and social hierarchy, essential for labor in agriculture, crafts, and domestic service.

- How Slaves Were Acquired: Primarily through warfare (prisoners), debt (selling oneself or family members), or birth to enslaved parents.

- A Duality of Status: The Code treated slaves both as property (they could be bought, sold, and inherited) and as persons (they possessed limited rights, such as the right to marry and the possibility of manumission).

- Key Legal Principles: Penalties often varied based on the social status of the offender and victim, showcasing the tiered justice system. Principles like "an eye for an eye" (lex talionis) were prominent.

- Lasting Impact: The Code set precedents for written law and legal systems, influencing later civilizations and contributing to ongoing discussions about justice, equality, and human rights.

The Dawn of Written Law: Hammurabi's Vision for Babylon

Picture ancient Mesopotamia, a fertile crescent brimming with life, innovation, and, inevitably, conflict. It was here, amidst a landscape of evolving city-states and nascent empires, that a singular ruler emerged to consolidate power and establish an enduring legacy. Hammurabi, the sixth king of the First Babylonian Dynasty, ascended to the throne around 1792 BCE. Over his impressive 42-year reign, he transformed Babylon from a regional power into a dominant force, extending his empire's reach across Mesopotamia.

But Hammurabi's ambition wasn't confined to military conquest alone. He understood that a vast, diverse empire required more than just might; it needed a unifying framework, a common understanding of justice and order. This conviction led him to commission what would become one of humanity's most significant legal achievements: Hammurabi's Code.

This wasn't just a collection of decrees; it was a systematic attempt to regulate nearly every facet of life, from commerce and family matters to criminal offenses and, critically, the intricate relationships surrounding slavery. The Code aimed to create stability, ensure economic prosperity, and cement his authority as a righteous king chosen by the gods. To truly grasp the complexity of this ancient world and its foundational documents, you might want to [Explore the Tigrismese hub](placeholder_link slug="tigrismese" text="Explore the Tigrismese hub").

Babylonian Society: A Hierarchy of Status and Power

To understand Hammurabi's Code, we first need to understand the society it governed. The Babylonian Empire was a complex tapestry of social strata, where an individual's status dictated much of their life experience. At the top were the king and nobility, followed by a class of free citizens, including merchants, artisans, and farmers. Below them, forming a significant segment of the population, were the enslaved.

Slavery wasn't an anomaly; it was an integral, deeply ingrained part of the Babylonian social and economic fabric. It was defined, starkly, as a condition where individuals were owned by others and compelled to work without compensation. Slaves performed a multitude of roles vital to the empire's functioning: they toiled in the fields, producing food; served in domestic households, maintaining daily life; and contributed to skilled trades, building infrastructure and creating goods. Their labor was the silent engine powering much of Babylon's prosperity.

People became slaves through several avenues, often through no fault of their own. War was a primary source, with vanquished enemies and captured populations being reduced to servitude. Debt was another pervasive pathway; individuals facing financial ruin might sell themselves or family members into temporary, or even permanent, bondage to settle their obligations. Lastly, the status of slavery was inherited: children born to enslaved parents automatically became slaves themselves. It’s a sobering reminder of how fate could be sealed by circumstance. If you're interested in how this elaborate social structure played out across different groups, you might want to [delve into ancient Mesopotamian social structures](placeholder_link slug="ancient-mesopotamia-social-structures" text="delve into ancient Mesopotamian social structures").

Decoding Hammurabi's Code: A Revolutionary Legal Framework

At its heart, Hammurabi's Code is an extraordinary document. Comprising 282 case laws, it offered detailed regulations for nearly every imaginable scenario. We're talking about provisions for economic transactions, intricate family law (marriage, divorce, inheritance), criminal offenses (theft, assault), and civil disputes. It provided a clear, albeit often harsh, framework that aimed to bring order to a burgeoning empire.

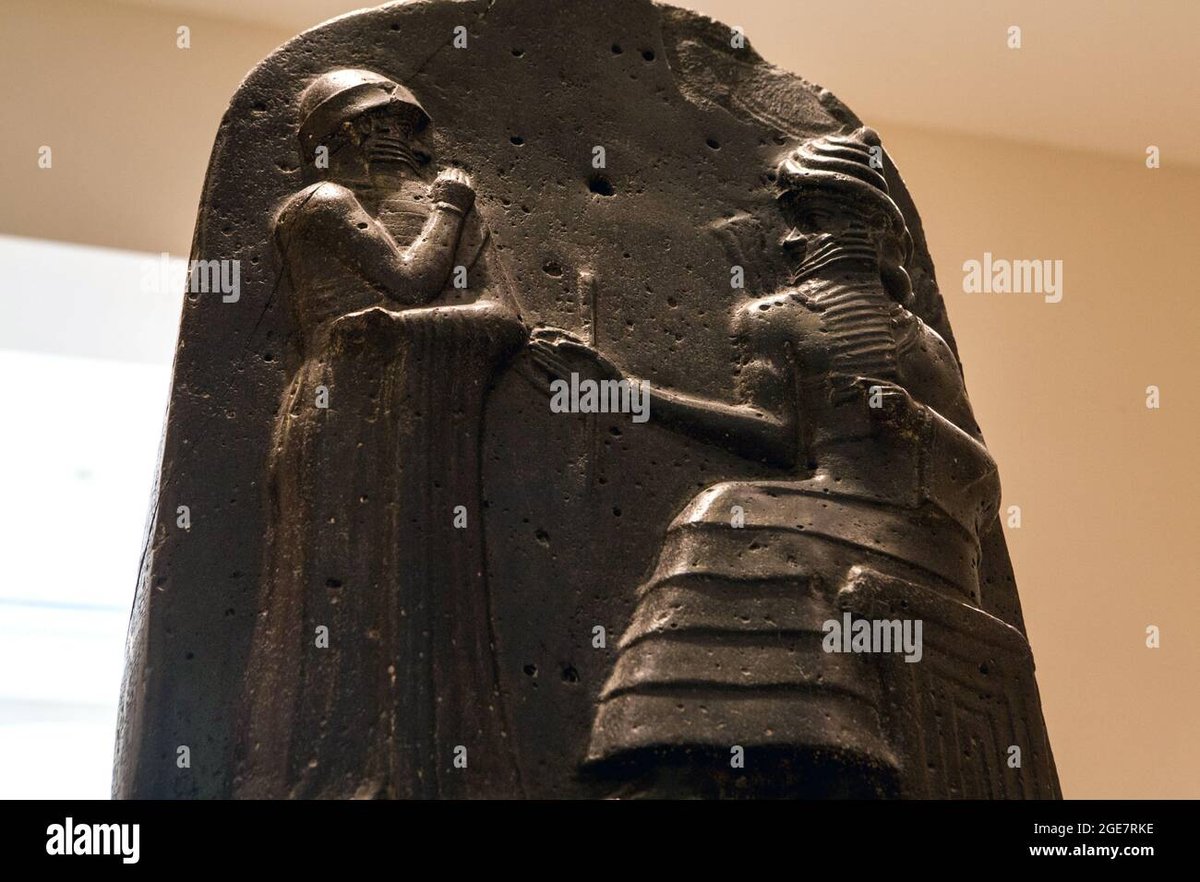

The principal source for our knowledge of this code is a magnificent black basalt stela, nearly eight feet tall, discovered in 1901 at Susa (modern-day Iran) by French archaeologist Jean-Vincent Scheil. This monumental artifact, now a prized exhibit in the Louvre Museum, is more than just a legal text; it’s a powerful symbol. Engraved at the top is a depiction of Hammurabi receiving the laws from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice, underscoring the divine authority attributed to the code.

Within its meticulously carved columns, the code introduces principles that would echo through legal history. Perhaps the most famous is lex talionis, often translated as "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth." This concept, while seemingly barbaric today, represented a significant step towards proportionate justice in an era where vengeance could often spiral unchecked. It wasn't always literal; sometimes it meant a monetary compensation equivalent to the injury. Another intriguing element was trial by ordeal, where an accused person might be subjected to a physical test (like being thrown into a river) to prove innocence, with divine intervention supposedly determining the outcome. This glimpse into their understanding of justice helps us [learn more about early forms of justice](placeholder_link slug="early-forms-of-justice" text="learn more about early forms of justice").

Slavery in the Code: Property and Personhood Intertwined

What makes Hammurabi's Code particularly fascinating, and indeed, complex, is its treatment of slavery. Unlike some later legal systems that viewed slaves solely as chattel, the Babylonian Code presented a challenging duality: slaves were undeniably property, yet they also possessed certain, albeit limited, rights as persons.

Slaves as Property: The Owner's Domain

There was no ambiguity in the Code regarding the ownership of human beings. Slaves could be bought, sold, exchanged, inherited, and used as collateral, much like any other possession. Laws addressed disputes over slave ownership, the return of runaway slaves, and compensation for lost or damaged slaves. This proprietary aspect underpinned much of their legal status, defining them as assets to their owners.

For example, if a slave ran away and was harbored by another person, the Code stipulated severe penalties for the harborer. If a "slave-hunter" returned a runaway, they were rewarded. This reinforced the idea that a slave was property whose value and labor belonged exclusively to their owner.

Slaves as Persons with Limited Rights: A Glimmer of Individuality

Despite their classification as property, Hammurabi's Code afforded slaves certain legal protections and pathways, demonstrating a recognition of their humanity, however conditional.

- The Right to Marry: Strikingly, slaves had the right to marry. Not only could a slave marry another slave, but a male slave could, under certain circumstances, marry a free woman. Law 129 states, "If a slave marries a free woman, the slave shall remain free, and the children shall be free." This particular law highlights a unique aspect: while the slave remained legally enslaved, their marriage to a free woman meant their children would be born free. This offered a potential, albeit indirect, pathway for future generations to escape the cycle of servitude.

- Possibility of Manumission: Freedom, though not easily won, was a possibility. The Code recognized and regulated manumission, the formal act of freeing a slave. Law 140 provides a glimpse into this process: "If a man wishes to free his slave, he must do so publicly and in the presence of witnesses." This stipulation for public declaration and witness corroboration indicates that manumission was a significant legal event, solidifying the slave's new status as a free person and preventing future claims of ownership. Such acts were often expressions of an owner's gratitude or religious piety.

- Protection Against Extreme Harm: While the penalties for harming a slave were drastically different from harming a free person, the Code did impose legal repercussions for certain acts of mistreatment. Consider Law 21: "If a man strikes a free man and kills him, he shall be put to death; if he strikes a slave and kills him, he shall pay a fine." The stark contrast in penalties (death for killing a free man vs. a fine for killing a slave) clearly illustrates the tiered justice system. Yet, the imposition of any penalty for harming a slave, even a fine, acknowledged that a slave was not merely an inanimate object that could be destroyed without consequence. It implied a degree of state interest in regulating the treatment of even the lowest members of society.

- Owner Responsibilities: Implicit in the Code were certain responsibilities of slave owners. While not explicitly listed as "rights" for slaves, the framework ensured owners provided basic care, food, and shelter, largely because a healthy slave was a productive asset. Extreme neglect or deliberate cruelty could, in theory, lead to legal action, although the practicalities of a slave seeking such justice would have been incredibly challenging.

This nuanced position underscores the complexity of slavery in ancient Babylon. Slaves were crucial to the Babylonian economy, acting as the bedrock for agriculture, craftsmanship, and domestic services. Understanding the mechanisms through which people entered and exited (or attempted to exit) this system helps us to [understand the nuances of debt slavery in the ancient world](placeholder_link slug="debt-slavery-ancient-world" text="understand the nuances of debt slavery in the ancient world").

Justice and Inequality: The Varied Hand of the Law

One of the most defining characteristics of Hammurabi's Code, evident in its provisions for slavery and beyond, was its system of stratified justice. The severity of a penalty often depended on the social status of both the offender and the victim. This wasn't a universal "justice for all" in the modern sense; it was a justice tailored to the rigid social hierarchy of the Babylonian Empire.

We've already seen this in Law 21: killing a free man meant death for the perpetrator, while killing a slave incurred a financial penalty. This principle extended to other offenses. If a free man struck another free man, the penalty might be a fine or physical retaliation. If a free man struck a nobleman, the penalty would be far more severe. And if a free man struck a slave, the penalty was typically a small fine paid to the slave's owner, not the slave themselves, reinforcing the slave's status as property.

This system, while ensuring some level of order, meant that "fairness" was often a relative concept, heavily influenced by wealth and social standing. Slaves, being at the bottom of the hierarchy and legally dependent on their owners, faced immense obstacles in seeking any form of justice against abuse or mistreatment from their owners or other free individuals. Their ability to testify or bring a complaint before a court would have been severely limited, making their practical "rights" fragile at best.

Manumission: A Glimmer of Hope for Freedom

While not common, the possibility of manumission offered a vital, if limited, pathway to social mobility for enslaved individuals. As outlined in Law 140, the process required a public declaration and witnesses, ensuring the newfound freedom was legally recognized and binding.

Reasons for manumission varied. An owner might free a loyal slave as a reward for long service, an act of piety, or even in a will. Debt slaves, particularly, might regain their freedom once their debt was fully repaid, or if a specific term of service, often defined at the outset, was completed. Freed slaves, though no longer owned, might still carry a certain social stigma or economic disadvantage. However, they were legally empowered to own property, enter into contracts, and participate in society as free citizens, albeit often in the lower echelons of the free population. This mechanism, though limited, offered a psychological lifeline and demonstrated that slavery was not always an immutable, lifelong condition for every individual in Babylonian society.

The Enduring Legacy of Hammurabi's Code

More than three and a half millennia have passed since Hammurabi’s Code was etched in stone, yet its influence endures. Its very existence marked a pivotal moment in human history: the codification of law. Before Hammurabi, legal principles were often oral, customary, or based on the whims of rulers. His code provided a consistent, publicly accessible legal framework, setting a precedent that would resonate for millennia.

The principles enshrined in the Code, from concepts of retribution to the structured approach to justice, can be traced through subsequent legal systems, informing the Roman law, Judeo-Christian legal traditions, and even, indirectly, aspects of modern jurisprudence. It stands as a testament to humanity's early attempts to grapple with complex questions of right and wrong, crime and punishment, and the delicate balance required to govern diverse populations. To truly appreciate its impact, it's worth taking the time to [examine the evolution of legal systems](placeholder_link slug="evolution-of-legal-systems" text="examine the evolution of legal systems") over time.

While the Code’s treatment of slavery and its stratified justice system are rightfully condemned by contemporary human rights standards, it nevertheless contributes to our ongoing discussions. It serves as a historical benchmark, allowing us to understand the long, often arduous journey towards universal human rights and the principle of equality before the law. By studying Hammurabi's Code, we gain insight into how ancient societies grappled with social stratification and the challenging task of safeguarding rights, even if those rights were unevenly applied. To deepen your understanding, you can also [compare it with other ancient legal traditions](placeholder_link slug="comparative-ancient-laws" text="compare it with other ancient legal traditions").

Beyond the Bronze Tablet: What Hammurabi Teaches Us Today

The Babylonian Empires and Hammurabi's Code remain a powerful mirror reflecting both the sophistication and the stark realities of ancient civilization. While we rightly recoil from the brutal disparities embedded within its laws—especially concerning slavery—the Code's very existence speaks volumes about the human drive for order, accountability, and the establishment of a common understanding of justice.

It reminds us that legal systems are not static; they are products of their time, reflecting societal values, economic imperatives, and the prevailing power structures. Hammurabi's effort to codify laws for an entire empire was a monumental undertaking, laying foundational stones for the legal principles that would evolve over thousands of years. From the public display of laws to the idea of "an eye for an eye," its echoes continue to inform debates about proportional punishment and the role of the state in regulating human behavior.

As you reflect on Hammurabi's legacy, consider how far our understanding of universal human rights has come—and how much further it still needs to go. The journey from stone tablets to international charters is a long one, but each step, including those taken in ancient Babylon, adds a crucial chapter to the story of justice and human dignity. By studying these ancient precedents, we not only understand the past but gain invaluable context for shaping a more equitable future.